Posts Tagged ‘mind’

The mind works tirelessly to keep us in line. It talks to us, ceaselessly chattering. It tells us we’re good or we’re bad or we’re right or we’re wrong, we’re gorgeous or we’re hideous, we’re wonderful or we’re worthless. Sometimes it tells us all these things within the span of a single moment.

It gives us all this conflicting information because it’s instantly reactive, like a startled cat. It doesn’t always understand exactly why it’s threatened, and it often reacts before it can even find out, to keep us safe and protected.

There are adaptive reasons for all this, of course, and our mind is to thank for our survival. Its understanding of how to behave has helped keep us alive and fitting into our families, schools, culture. It has analyzed our world and come to understand what’s expected of us, then programmed itself to keep repeating all the messages it deems necessary to help us survive.

Problem is, many of these messages are very outdated. Or, at the very least, could use some reinspection.

The mind is often right that we can’t just, for example, jump up in the middle of class to go play outside in the dirt. But we can also use these opportunities to gently challenge these ideas by asking questions: Why not? If not now, when? Where? Is there a place where this could be allowed, indulged? If not, why not?

Thoughts are merely thoughts, after all, and not problematic when they’re recognized as such. It’s when we unquestioningly believe them to be true that we run into difficulty, because they’re so often obsolete ideas suited to situations that haven’t been relevant for years, or even decades.

A main function of the mind is to control the body, which is also essential. After all, we need to wait sometimes to eat, to sleep, to use the bathroom, and the mind helps the body manage that.

But because the body also has important urges and needs, it’s necessary to let it have its say, to find a way to do what it wants to do. The body has a different kind of intelligence than the mind does, with messages that are just as vital for the full living of our lives. We’re taught to ignore our bodies, to push them down, to tame them. But no animal–and your body is an animal–can ever be fully tamed. Its natural way of operating is to move, to open, to vocalize, to take its place in space, and it must do that. It must.

To think our bodies can or should be wholly tamed is a dangerous and pernicious notion. Our bodies are treasure troves of information and understanding, just waiting to be accessed. To close ourselves off from their messages is to squander one of the greatest gifts of being alive.

Where have you tamed yourself, and where might you open up? Where could you listen more deeply? What might you hear if you did?

Sunlight streams through the open window next to me, and the early spring breeze carries a fresh, inviting brightness with it. Reluctantly I turn my body back in toward the classroom, where in contrast the light feels paltry, dim, inadequate.

I focus my attention on my notebook, endeavoring to catch up. The professor speaks in his usual engaging way, and the other students are present and alert.

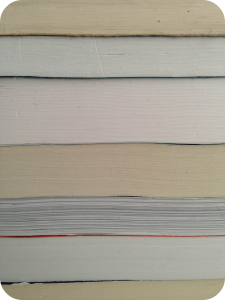

We’re talking about Wittgenstein, and it’s unbearable. I’m not entirely sure why, but my mind feels pressed down upon by the weight of other people’s thoughts. It’s as if I’ve been trying to carry all of them stacked upon one another like thousands of aging, translucent pages–feeble, fragile, no longer alive with relevance.

My gaze drags back to the day outside, to the bright reflectiveness of the soft blades of grass, the buds on each tree branch urging themselves outward. I ache to join it all. My body is nearly in revolt, refusing the reality of the room I’m in, longing to get out.

I notice how the roots of the trees clench the earth, like fingers digging into it, and have to fight the nearly irresistible urge to leave my chair and go kneel out there. Kneel on the slightly damp dirt and dig my hands into it, the way the roots of the trees cling to the earth but are also just part of it, extensions of it. As am I. Just an extension of all that dirt, that grass, those roots, the buds, the branches, the sunshine.

I want to put my hands in it, to feel the texture of the soil, to smell it, to know what it’s like to get my own roots in there. To dirty myself, to be part of it. Part of the day, part of my own life.

It’s almost erotic, this yearning, and I find myself fidgeting in my chair. I want to engage, and not with thoughts or ideas. I want to engage with the dirt of the place where I live. I want to mix with the life that’s in evidence right out there, just feet away from where I sit.

My mind controls me, keeps me in my seat, but I can’t concentrate. My only thoughts are of what my body wants and needs–to get out as soon as possible.

After class, I go lie in the grass, resting my head on the stack of books inside my bag. As overwhelming as the urge had been to be out here, I can’t just kneel and dig my hands in the dirt. What would the people passing by think?

So I lie still, looking up at the sky between the branches of the trees, imagining what I’ll do with my life once I’ve got the degree and am free of the confines and the ideas and the rules and the way things always have to be just so. Free to dig my hands into whatever I want.

Our whole selves are instruments.

Fully engaged–with our minds, bodies and emotions open and functioning–we are instruments perfectly calibrated to sensing the world around us. When we’re in alignment, we effortlessly feel into our world, interact with it, live as a fully integrated part of it.

Because in actuality there’s no way to disconnect our own wholeness from the wholeness of everything. It’s all connected, an infinite and vast web, wholly incomprehensible in scope and yet also somehow astonishingly accessible to us.

What we can do, however, is disconnect from our own wholeness.

When all is functioning well, our interconnection with the world is palpable on a visceral level, and accessible directly through our senses. Our bodies are constantly taking readings on our surroundings, physically noticing what might be dangerous, or what might be enjoyable. Situations are called to our attention through sensations or emotions–fear, anger, interest, attraction.

When our attention isn’t focused on the body’s messages, it can be easy to just let these things pass unnoticed, to miss essential cues that might otherwise save us inconvenience or even injury, or might lead us to a fulfilling experience.

When we ignore this information, as we often do, we shut ourselves off from the wholeness of our lived experience. From an early age we’re taught to let the mind take precedence, to allow it to cut us off from other ways of knowing and interacting. Without us even consciously noticing, the mind directs us to sit still, to wait, to persist, to keep quiet, to do as we’re expected to do.

These are all necessary skills, of course, and important to be able to rely on in certain situations. But they’re not always necessary or called for. We learn to police ourselves diligently and thereby cut off parts of our own experience and knowing that could help us live our lives more fully.

The body and emotions, when listened to, open up whole new vistas that we may have forgotten existed. The experience expands, widens, deepens, and the world becomes not the place we thought we already knew, but something vibrant, mysterious, fascinating. And as we let ourselves notice and engage in this way, we find ourselves guided by an inner knowing that has nothing whatsoever to do with rational thought.

This can lead to simple coincidences–the finding of a thing we’ve been searching for–or it can lead to circumstances much less explicable, much more engaging. It can lead us to new thoughts or ideas, to adventures we’d never otherwise have had, to travels we’d not have dared undertake.

The most beautiful aspect of intuition, perhaps, is the fact that it’s available to all of us, all the time. At any moment your whole self is waiting for you to listen and respond to it. And every time you do, with every action you take in response, the voice of your intuition becomes stronger, bolder, better able to support you.

What’s there right now, waiting to be sensed?

I cross the street from Nørreport Station and step into Fiolstræde, enjoying the light of the early spring morning on my well-worn path to school. A man stands eating a sausage in front of the hot dog wagon. Cyclists roll over still-wet flagstones, and pigeons loiter hopefully in front of the vegetable stand. What was once foreign is familiar now, and dear to me.

Normally I pass the bookstore on the corner with some curiosity, but I almost never go in. There’s a book I’ve had in mind, though; a particular passage in a book, actually. I’ve been fruitlessly searching Copenhagen’s bookstores for it since shortly after I arrived nine months ago, and suddenly feel the urge to try again.

The clerk looks dubious when I tell her the title of the book, but asks for a few minutes to research whether or not they carry it.

I make my way through the Danish titles and settle in the children’s section, where a beautifully illustrated copy of H.C Andersen’s stories lays waiting to be read. Much to my delight, words that would’ve made no sense just months ago unfold into meaning. I’m still engrossed when the clerk approaches, looking apologetic. The book could be imported for me, it seems, but at a steep price. I thank her and step back into the street.

At idle moments throughout the day I try to excavate parts of the passage from my mind, but I know it’s still not right. Frustrated, I go to the school’s library and run an internet search, but turn up nothing.

Late that afternoon on the train home, I try to focus on my reading but end up staring out the window instead. It’s gently raining again, and the clouds hang low in the sky. Drops of water slip down the window, only slightly obscuring the passing scenery. I watch the red-tiled houses, the streets, the cars, the shops. A pair of teenage girls walk arm-in-arm. A mother pushes a large black pram across an intersection. All the while my brain works, trying to tease out a clearer memory of the passage I’ve become stuck on.

Descending the stairs in the station, I pause before turning toward home and instead go in the other direction. I’m not entirely sure why, but I head past the grocery store and the entrance to the shopping center.

My eyes sweep across the square and my attention catches on the glass enclosure of the library’s entryway. I’ve only been in once or twice, but I’m unquestionably drawn to it now. There’s no chance of my book being there, I know, but it’ll be fun to look.

The English section is small, tidy, spare. I peruse the shelves, curious. There’s nothing to surprise me there: Austen, Dickens, Hemingway.

But, suddenly, there–on the second lowest shelf, in a small library in a suburb of Copenhagen–stands the very familiar spine of my much longed-for book.

Right where I’d never hoped to look.

The gifts of the senses are easily taken for granted. Surrounded as we are by constant stimulation, we forget to pay attention, to notice, to appreciate what we experience.

Bombarded by sound, we shut down to the ordinary noises we hear–a TV nattering in the background, the ocean-mimicking whooshing of passing traffic. Casually, we overlook sights that would have arrested and enthralled any of our ancestors just a few generations back–a man walking down the sidewalk talking on the phone, a woman casually flicking through a magazine on her iPad as she waits for the bus. Common miracles.

Passing a corner restaurant, we catch the scents of foods we didn’t know as children. We taste combinations of flavors never before considered possible that now seem run of the mill.

And our whole world has been smoothed over. Not just the pavement laid down nearly everywhere we care to go, but the very surfaces we touch on a day-to-day basis are more often than not smooth and uninteresting to the touch. Fleece jackets, credit cards, smartphone screens–so much of what we place our hands on is designed to feel as delightful–or unnoticeable–as possible.

But sometimes the animal self perks up, senses alert. Like when we go out into the day just after a rain. Maybe there’s the smell of dirt, wet and invigorated. Or the sound of a bird calling out as it passes overhead. The sight of high tree branches rustling in the post-rain wind, the feel of the newly-visible sun on exposed skin. All the world awake again.

These things are often present, of course, but we forget. We forget because we perceive so much all the time that it’s hard to keep perceiving. We’re overwhelmed, overloaded. We have to back away, to shut down a bit, to dull ourselves, so that it all doesn’t become too much.

We’re just animals, after all. Miracles of blood and bone that can only change so quickly. We startle, we tire, we grow hungry. All the effort put into smoothing out the world around us can’t shift the essential animal nature of each of our bodies, or its needs.

To seek out textures sometimes, to find the things we love to sense, is an adventure worth having. What do you sense that moves you in some way? Can you let these experiences in? What’s it like to sense, to truly experience what’s there? What’s worth knowing, worth remembering, worth integrating on the ride of this human life?

What happens if you turn on some music and dance exactly the way you want to? Or if you scoop up paint with your fingers and smear it on a canvas? If you try cooking a favorite recipe of your grandmother’s? If you run your hand over the bark of a tree trunk? If you stop and listen–really, actually listen–to the person speaking to you?

What happens then? Is it smooth? Bumpy? Scary? Exhilarating? What happens then?

September, 2012

Tokyo, Japan

Kneeling on the floor blindfolded, I reach out with my right hand, searching. I have a sense of the general area of what I’m looking for, but can’t quite locate it. My hands grope in the air, sightlessly seeking.

And then a finger touches the smooth wetness of paint glopped onto my palette. Ah!

I smile, dipping the fingertips of both hands into the unseen colors, savoring their coolness. I lift my fingers, the paint clinging to them, and reach each hand out to either side of me, putting them down onto the rough white canvases waiting there.

I can picture the blank surfaces in my mind’s eye, imagine them being smeared with the reds, yellows and oranges coming off my fingertips, but not knowing for sure what they look like is exhilarating.

The beat of the music picks up and with it I dip my hands to the palette again, this time mixing the colors by gently rubbing my fingertips together. I put my hands to the canvases, moving with the beat, letting the music inform my every gesture, letting it become part of the painting.

Leaning again to the palette, I pull up more paint, scooping with my fingers and delighting in the sensation. Again I reach down to the canvases, body rocking, hands echoing the movement of the rest of my body, my fingers the very focus of the dance.

What’s happening underneath them? My only perception of the paint is through the touch of my skin, and in the unfamiliarity of this way of knowing I’m swept into a joyous reverie. I don’t know exactly what’s happening and I love it; I can’t see what kind of marks I’m making and I don’t care. I only want it to keep going, only want to keep living this feeling, keep experiencing this interlocked dance of body, paint and music.

The sensitive tips of my fingers are starting to become slightly bothered by the uniform bumps of the canvas, their subtle roughness more and more apparent as I continue to touch them.

Undeterred, I move my hands to the paint again, this time meeting my palms in front of my chest, feeling the paint warm with my touch. I wonder what color they are now, my hands. The urge to peek at what’s happening suddenly becomes nearly too much to resist, and yet I know that looking would somehow break the spell of this moment, and so hold back.

When a break comes in the music I find a natural pause too and lift my forearm to my face, pushing the blindfold from my eyes. To my right and to my left lie two paint be-smudged canvases, lively and glowing. Their frenetic energy pops out at me, a visual representation of the joyous wave I just rode.

They’re just finger paintings, yet caught in them is something else too. Dynamism, motion, energy. The pure bodily enjoyment of movement and touch.

You might as well know the truth: meditation always sort of scared me. There was the stillness and the silence and then the thoughts. All those thoughts that would roil up and ask to be looked at, ask to be seen.

What I didn’t get–the fundamental misunderstanding I brought to meditation–is that the practice is not to quiet the thoughts or make them disappear. The practice is to recognize them, thank them, and let them go at their own pace.

What the monks on Mount Koya may have known that I didn’t is that the thoughts running through our minds are not who we are. We are not those thoughts, but the observers of them. The thoughts themselves pass like clouds in an otherwise clear sky, and the observer remains there, watching.

The clouds simply are. Just as we don’t judge clouds as good or bad, right or wrong, the practice of meditation asks us to treat our thoughts in much the same way. The thoughts that float or skip or tumble into our minds are a part of our humanity, part of our animal selves, and they serve many very important purposes. But they’re not who we are.

Through meditation, we can connect with the true essence of ourselves–that observer–and watch the thoughts do their thing. The more we do this, the easier it becomes to recognize the reality of the situation: that the thoughts are simply thoughts. There’s no need to give them any power, any credence.

And therefore there’s no need to resist them. It doesn’t actually matter much whether they seem to us to fall into the broad categories of positive or negative. They will pass. It’s the resistance of them that causes pain.

So this is something else those peaceful-looking monks may have thoroughly integrated that I had not yet even considered: that all our thoughts and feelings are here to be seen. That’s all they really want. Our fear is that if we stop to look at them, they’ll suck us into some black hole of pain from which we’ll never emerge.

But really they’re just messages to us, here to serve us. Our fear asks us to look inward, our anger teaches us to look at our boundaries, our sadness shows us how to release. They’re beautiful and vital messages from our innermost selves, and they’re here to help. Even the “negative” ones, the scary ones. Sometimes especially those.

When we resist thoughts and feelings, it’s like trying to escape from a Chinese finger trap by pulling hard in opposite directions. Not only does it prevent the ends we have in mind, but it leads to frustration and even mild panic. It’s only when we relax our fingers and push them inward–when we give the thoughts and feelings the attention they need and then let them pass on their way–that we become free. Completely free to relax back into the wholeness of who we really are.

May, 2003

Mount Koya, Japan

I hate this. I fucking hate this.

The thought curled up into my consciousness like a coil of smoke from the incense burning on the dais. The monks leading our meditation practice sat silent, as did everyone else. My thoughts were the loudest things in all existence.

Sitting back on my heels, a position called seiza in Japanese, my legs had already lost all sensation. As unobtrusively as possible, I wiggled myself back and forth. It helped momentarily, but then the tingling deepened, expanded, painfully filling my experience so no other thought could enter.

Opening one eye, I snuck a look at the friend I’d come with. She was sitting in seiza with seemingly effortless ease, breathing deeply, her stomach expanding and contracting with a naturalness I envied.

I’m not supposed to be here. I’m not cut out for this.

It’s not that I’d planned to be there. Having arrived in Japan less than a month earlier, I hadn’t made any plans for the holiday week that straddles the end of April and beginning of May. When my coworker mentioned the trip she was taking to Mount Koya, I’d asked if she minded me tagging along. She’d seemed happy to have a companion, and I’d been thrilled with the trip up to that point.

But somehow, sitting there trying to keep completely still, I felt that everything about the situation was wrong. I wanted to get up and run, twirl, kick, move. Feel my body. Shout. Scream, even, just to feel anything at all.

How much longer?

We’d trundled up there in a very old train, only a few cars long. It’d been charming and beautiful, climbing the mountain that way, watching the towns and villages pass by with their tiled roofs and hilly streets. As we’d climbed it’d gotten colder and colder until, at the very top, the weather was almost winter-like even as spring had fully descended at the mountain’s base.

Upon our arrival, a kindly monk had led us to our small tatami room with a sliding door, two futons stacked on the floor, and a kotatsu, the room’s only heating source. Before dawn the next morning, the same monk had come to get us for meditation practice. Following him along the path tracing the rock garden, I’d been excited to experience sitting in meditation. But the sitting itself felt interminable, unbearable, physically impossible.

What’s wrong with me? I can’t even meditate for half an hour. I suck in every way.

The taunting of my mind was far more painful than the experience in my body. Comparing, complaining, worrying, wondering, my mind mocked me ceaselessly, telling me how bad I was, how stupid. How I’d never be right. How everything I was doing was wrong.

I cracked open my eyes again to surreptitiously study the faces of the monks sitting in front of us, peace saturating their features. What was it they were experiencing? And could I ever find it too?

We all have these moments sometimes, don’t we? Fleeting, maybe, and rare, but we all have these moments of suddenly noticing the fact that we’re alive. After days or weeks, months or years of having all but forgotten, there’s a jolt of recognition and there we are, electrified with the awareness that all of life is pulsing around us. That the moment where we stand is the only moment, and that in that moment everything is connected to everything else.

They often show up when we’re caught off guard, these moments, when something unexpected happens or when for one reason or another we find ourselves acutely noticing our surroundings. When beauty catches us unawares and suddenly we expand into it, tiny energy-fine tendrils of ourselves keenly aware that they exist in a vast, infinite network of tendrils that all live and beat and breathe together. This is the deepest truth of what we know at a visceral, cellular level. That we are alive, that we are aware, that we are all connected to each and every thing in existence in some achingly, powerfully beautiful way. And we feel it in a way that is incomparable to any other feeling.

And, if we pay attention, we notice that it is a feeling rather than a thought. It’s not brought about by logic, by careful dissection, by intense mental focus.

Let me be clear: I’m a big fan of logic and reason. They’ve brought us countless gifts, and they’re valuable beyond measure. But they’re only capable of accessing part of the world, and therefore part of the truth. When we restrict ourselves to operating solely within their realm, we close off vital ways of knowing that are just as valuable, just as interesting, just as compelling.

This is something that we do regularly in our culture, though; we shut down our bodies, shut down any way of knowing that isn’t rooted in logic. Many of us spend our days living in a mental world, disconnected from the awareness of our bodies and the parts of ourselves that don’t “make sense.” As we grow up we find it easier and easier to sort, to categorize, to believe that we have it all figured out. And when that’s the way we approach the world, our vision shrinks and narrows until our way of seeing the world is so cramped as to barely allow anything new to enter. When this happens we think we already know what we need to know, and anything that doesn’t fit into our worldview can be discarded as irrelevant, uninteresting, or just plain wrong.

But when the chance comes to take a step back, to re-enter the body and its moment-to-moment experience, fresh information is once again free to flow in, to bring us into the awareness of our whole selves–not limited to the selves of our minds. It’s all there in the ever loyal and patient body, accessible to us anytime we’re willing and able to feel for it.

Winter, 1986

Seven years old

Boots crunching through the fresh snow covering the backyard, I headed toward the woods, sunlight filtering down through the interlaced branches of the tall trees all around and up the hill. In the summer it would be shady here, only dappled light touching the ground through a roof of tremulous green. But now all was bare, and the sun reached down to touch most of the snow that had fallen the night before.

My brother and I had been out to play just that morning, but after lunch he’d stayed in the warmth of the house to watch TV while I’d felt the pull back outdoors.

My eye caught the plastic playhouse that had been there for several years and that we rarely used anymore. Its colors were faded by sun exposure, the decals puckered and starting to pull away. As I opened the small half-door I saw that only a bit of snow had drifted in, not enough to cover much.

The winter sunlight slanted in the window, reflecting brightly off the snow on the bank that sloped up just outside. I sat in the small plastic chair and looked out, gathering my arms to my body to keep warm. My breath puffed out in clouds and I played with them, making them bigger, smaller, bigger again, watching the clouds appear and disperse in the space of one exhalation.

My attention caught on the bare tree branches, the sun skimming off them in a way that made them shiny and reflective. The branches themselves were beautiful, naked as they were, locked together and coming apart with the breeze, a tangled web of dormant life. The way the sun fell on the perfectly fresh snow made it glitter, and there were colors in it dancing, almost twinkling, that I’d never before appreciated in snow. Flashes of green, pink, orange, blue, tiny crystals of color bounced their light over the early afternoon.

Stillness wrapped all around. I stopped to listen, trying to find anything familiar–a car, a TV, a human voice, the skittering of a squirrel. There was only the very slight rustle of the wind in the branches high above me.

And in that near-silence, a sense of deep and boundless peace overcame me. Everything–everything–shimmered and quivered with life. Everything had a current running through it, and it ran through me too. My body shivered, but not with cold–with recognition. With acknowledgement. With a feeling of seeing, of having been seen. With a feeling of knowing that I was part of all that was, that all that was was part of me. There were no words to it, no thoughts. Just feeling, just beauty.

I thought, I want to keep this, and that very second it began to fade, dissolving like a cloud of breath. Completely gone, as quickly as it had come, leaving a little girl sitting on a plastic chair in a plastic house, overcome with wonder and awe.